Discrete physical properties are called “topological” because they arise from some underlying geometric constraint. For example, the orbital magnetic quantum number m of an electron counts the winding of the wavefunction around an axis and can therefore only be integral. This is in contrast to the momentum of a free electron, which can take on any value. In electrical devices, effects arising from topological properties can increase resilience to noise and have applications in quantum information and metrology. Here, we design and fabricate a simple quantum electrical circuit with remarkable topological properties that we measure using spectroscopy.

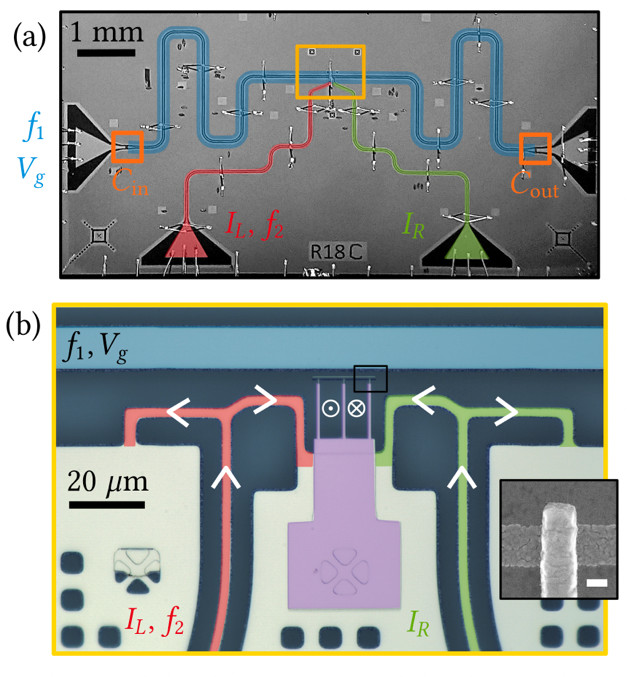

Figure 1: (a) Microscope image of BiSQUID device. A superconducting microwave resonator (blue) is coupled to a quantum circuit with three Josephson junctions, yellow inset (b), purple region. Inset: scanning electron microscope image of rightmost Josephson junction (scale bar 100 nm).

The superconducting circuit, called BiSQUID, consists of three Josephson junctions in parallel. The BiSQUID (Figure 1) acts as an artificial atom whose topological features are encoded in its excitation spectrum, the frequencies at which the artificial atom can absorb energy. When properly tuned with external voltages and currents, this spectrum has a distinctive structure of degeneracies. A degeneracy means that a photon can excite a single quantum state in two different ways. Using microwave techniques adapted from spectroscopy of real atoms, we probe these degeneracies and demonstrate how fabrication parameters dictate whether a BiSQUID will be topologically trivial or not (Figure 2). We identify two binary topological invariants: are there any degeneracies at all? If so, is the ground-state degenerate or are only excited states degenerate? We also identify an integer topological invariant which is equivalent to the orbital magnetic quantum number describing the winding of the wavefunction.

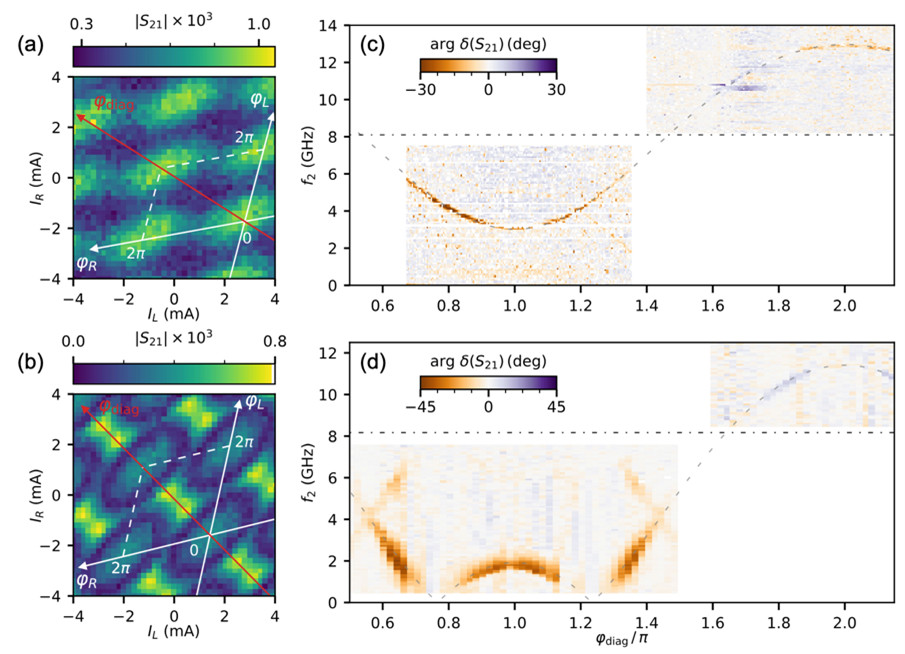

Figure 2: Microwave spectroscopy of topological invariants. In (a) and (b), the microwave response of the resonator is plotted as a function of two control currents changing the magnetic flux threaded by the BiSQUID. For the non-topological BiSQUID (a), there is only one inflection point in the unit cell (blue region inside diamond), whereas for the topological BiSQUID (b), there is a green hourglass shape inside the unit cell with two inflection points. Two inflection points indicate that there are degeneracies in the spectrum. (c,d) shows two-tone spectroscopy of the two devices as a function of a control flux. For the non-topological BiSQUID (c), the excitation spectrum is gapped: the spectral line does not go to zero frequency. For the topological BiSQUID (d), the spectrum heads toward zero at two values of the control parameter. Although we cannot excite the transition at low frequencies, extrapolation of the measured data indicates the degeneracy points.

Measuring the topological properties of a BiSQUID is a first step toward exploiting topology in more complicated circuits.

Reference:

Spectral signatures of nontrivial topology in a superconducting circuit,

L. Peyruchat, R. H. Rodriguez, J.-L. Smirr, R. Leone, and Ç. Ö. Girit, Phys. Rev. X 14, 041041

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.14.041041

Contact CEA-SPEC : Caglar Girit (SPEC/GQ)