Researchers at the Institute of Electronics, Microelectronics and Nanotechnologie (IEMN / CNRS – Universités Lille 1 and Valenciennes, Institut supérieur de l’électronique et du numérique-ISEN) and the Solid-state Physics Division at the French Atomic Energy Agency (CEA), have succeeded in making transistors from carbon nanotubes on a silicon substrate. The transistors, which are mainly used as automatic switches, can reach cutoff frequencies of 30 GHz [1], which improves by a factor of 4 the previous record obtained by the same teams in August 2006. This result opens up new prospects for mainstream applications which require high operating frequencies.

The aim of molecular electronics is to develop components based on various types of nano-objects, and information processing systems. This is the kind of technology which, for instance, is used in display systems such as electronic paper. To make the basic components, organic compounds such as polymers are generally used, and these are deposited on the surface using simple processes, identical to those used in techniques for printing on paper (ink jet). However, such materials have low electron mobility. This limits the frequency at which the current can be carried, and therefore the switching frequency of each basic transistor, which in turn limits the applications of the technology. Carbon nanotubes, on the other hand, are characterized by high electron mobility, which is compatible with high-speed electronic applications, and in addition, they can be deposited using inexpensive technological processes.

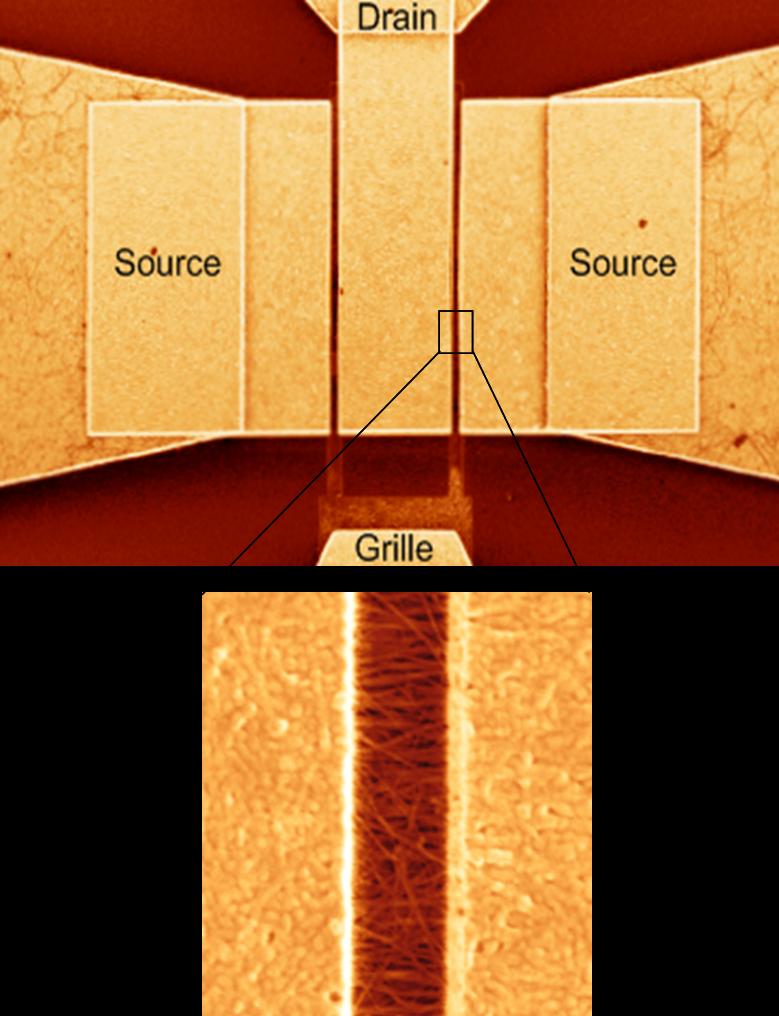

Researchers at IEMN and CEA, with backing from the National Research Agency (ANR)‘PNANO HF-CNT’project, used a technique known as dielectrophoresis to obtain uniform deposition of a large number of aligned nanotubes. They succeeded in making transistors based on carbon nanotubes on a silicon substrate which reached cutoff frequencies of 30 GHz. This result improves by a factor of 4 the previous record obtained by the same teams in August 2006. The process used can be carried out at room temperature, which also makes it totally compatible with other inexpensive substrates such as glass, plastic, etc, and opens up new prospects for mainstream applications which require high operating frequencies.

A. Le Louarn, F. Kapche, J.-M. Bethoux, H. Happy, and G. Dambrine

V. Derycke, P. Chenevier, N. Izard, M. F. Goffman, and J.-P. Bourgoin

Applied Physics Letters, 90, 233108, Juin 2007.