Pages scientifiques 2011

Cette thématique pluridisciplinaire fait partie intégrante du domaine de l’électronique organique. Elle fait appel, entre autres, aux compétences relevant des domaines de la chimie et physico-chimie, de la physique des semi-conducteurs et de la caractérisation optique et électrique de dispositifs électroniques. Cet axe de recherche propose le design moléculaire, la synthèse, la caractérisation et l’utilisation de matériaux innovants comme composants actifs de diodes électroluminescentes organiques. Certains de ces matériaux contiennent des ions lanthanides qui possèdent des couleurs d’émission dans le visible et le proche infra-rouge d’une pureté incomparable. Les applications de ces dispositifs opto-électroniques sont très variées, elles vont de l’éclairage aux appareils à visée nocturne, en passant par le balisage et les écrans ultra-plats. En particulier, la très grande légèreté des dispositifs que ces matériaux permettent d’élaborer en fait des éléments de choix pour l’électronique embarquée.

Nanoparticles, considered as tools or analytes, have been the focus of much attention in Analitycal Sciences Research these last years. As tools, they are extractants, surface modifiers, etc…. as analytes, they require quantification just as bulk solid or dissolved materials but also physical and chemical characterizations (size, surface properties, shape, …). Our activities cover several aspects:

- the determination of the amount of suspended nanoparticles at low levels (few ng/L) in environmental liquid samples,

- the study of interaction between nanoparticles and neutral hydrophylic organic polluents by capillary electrophoresis,

- the design of new analytical devices such as the complementary measurement of nanoparticle size and elemental composition (monodisperse droplet ICPMS).

Equations intégrales et simulations Monte Carlo moléculaires

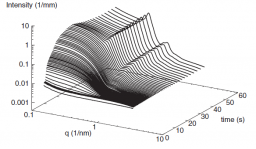

Toute la nouveauté tient dans le qualificatif "moléculaire" : Il s'agit de calculer les propriétés d'équilibre, thermodynamique et de structure pour des fluides de particules non sphériques. En clair, comment calculer à partir d'un potentiel de paires v(12) entre 2 particules la fonction de distribution de paires (pdf) g(12), l'équation d'état P(r), le facteur de structure S(q), l'intensité diffusée I(q) en diffusion de rayons X ou de neutrons… pour une température T et une densité ρ données ?

La difficulté par rapport au cas "atomique" très classique et bien maîtrisé depuis 30 ans des particules sphériques est que maintenant (12) représente non seulement la distance r entre les 2 particules 1 et 2 mais aussi l'orientation relative Ω de chacune d'elles et du vecteur les joignant, g(12)=g(r,Ω). Plusieurs cas de telles particules anisotropes sont rencontrés dans les recherches effectuées au LIONS. Il peut s'agir de particules linéaires comme les sphères dipolaires ou encore les micelles de tensioactif cylindriques ou ellipsoïdales, les nanotubes d'imogolite… dont l'orientation relative est repérée par 3 angles d'Euler. De manière plus complexe, il peut aussi s'agir de particules non linéaires comme les modèles type SPCE (interaction site-site) de molécules d'eau (H2O vu comme 3 sites à charges partielles) ou comme les "molécules colloïdales" de tétrapodes constituées d'un cœur de silice et de 4 sites de latex en positions tétraédriques. Cette fois-ci, 5 angles d'Euler sont nécessaires !

En mécanique statistique des liquides, deux approches théoriques très complémentaires sont en compétition depuis les années 1960. La 1ère utilise la simulation numérique Monte Carlo (MC) ou la Dynamique Moléculaire, la 2nde résout l'équation Ornstein-Zernike (OZ) avec une équation intégrale, généralement du type HNC (hypernettted chain). La 1ère est exacte, en ce sens que la pdf obtenue au final correspond exactement, en théorie..., au potentiel de paires v donné en entrée. La 2nde apporte une solution approchée, car l'équation HNC n'est qu'une approximation. La 1ère est "facile" à programmer et ne demande aucun artifice (des codes très versatiles sont même proposés sur le web gratuitement), la 2nde peut demander des codes lourds faisant appel à des techniques d'analyse numérique pointues. Mais, les calculs pour obtenir la solution exacte (1ère méthode) sont très longs pour des particules anisotropes, souvent au delà de la limite des capacités des ordinateurs de bureau puissants actuels. Il faut une heure, une nuit, un week-end, une semaine… pour sortir des pdf (pair distribution funciton) ou des intensités diffusées I(q) dont le bruit statistique reste raisonnable.

Au contraire, la 2nde, grâce aux codes très robustes et puissants, est résolue sur ordinateur en quelques secondes ou minutes et les courbes finales sont vierges de bruit statistique. En conclusion, la simulation n'est utilisée que pour quelques cas typiques qui servent de référence et l'équation intégrale est résolue de manière plus systématique pour, par exemple, le dépouillement de spectres expérimentaux. La comparaison des deux techniques permet d'estimer le degré d'approximation de HNC et, si nécessaire, de montrer la direction à suivre pour améliorer la résolution de l'équation intégrale. L'équipe du LIONS a une longue expérience de ces deux techniques pour des particules sphériques (30 ans pour HNC, 15 ans pour MC) et les a développées dans les 5 dernières années pour des particules anisotropes à l'occasion du projet ANR SISCI.

Simulations Monte Carlo (MC)

Cette technique est bien-sûr très classique. Il s'agit de placer N (100-1000) particules dans une boîte cubique de simulation dont la taille est imposée par la densité et de générer une suite (lire plusieurs millions) de configurations en accord avec le potentiel d'interaction et la température. Il "suffit" alors de construire un histogramme des distances (et orientations!) observées pour obtenir la pdf. Seule remarque centrale: la simulation numérique particulaire est un problème essentiellement de bruit statistique qui décroît comme la racine carrée du nombre de configurations observées (indépendantes). Donc, si au bout d'une nuit de calcul on obtient des courbes peu jolies dont on veut diviser le bruit par 10, il faut continuer la simulation pendant … 2 mois!

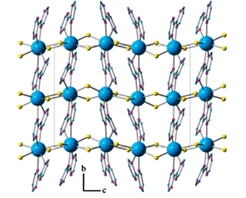

Le LIONS utilise actuellement MC pour des fluides dipolaires qui sont des modèles simplistes de l'eau (voir page "effets spécifiques ioniques") et sur les molécules colloïdales de tétrapodes. Ce denier cas est illustré ici: les tétrapodes sont fortement imbriqués au sein de la cellule et le spectre de diffusion, donné pour 2 nombres N de particules, est compatible avec une structure diamant de l'organisation.

Welcome to Complex Liquid Thermoelectrics Research group

NEW!!! Internship position (4-6 months, experimental) for thermally chargeable supercapacitor develoment and characterization

M2 level, starting Feb/March 2020. Possible continuation as a PhD candidate from Fall 2020.

To know more click HERE

Who & What

We study thermal-to-electrical energy conversion phenomena in liquids by combining experimental techniques from physics, physical chemistry and electrochemistr. It is an exciting new field of research that is attracting increased attention as an alternative solution to semi-conductor based thermoelectric materials. The underlying physics , the types of complex liquids and possible future application paths are described below.

Also....

Please visit our MAGENTA project page https://www.magenta-h2020.eu

A member of NANOUPTAKE– Overcoming Barriers to Nanofluids Market Uptake (COST Action CA15119)

Thermoelectricity at a glance

The application of a temperature difference ΔT across a solid conductor causes mobile charge carriers to diffuse from hot to cold region, giving rise to a thermoelectric voltage V = -Se∆T. The prefactor Se is called th thermopower or Seebeck coefficient since the discovery of this phenomenon by Seebeck in 1821. This enables the conversion of heat to electricity.

In ordinary metals like copper, the Seebeck coefficient Se is of the order of 10 μV/K. In the mid 20th century much higher Seebeck coefficients of a few hundreds of μV/K were obtained in low-gap semi-conductors, and those materials are still the object of intense research activities, with the perspective of converting low-grade wasted heat; e.g., body heat, car exhausts, industrial waste streams, solar heating, etc., into electric energy. Conversely, the application of voltage ΔV results in a temperature difference (the Peltier effect) such that the same material can be used as a thermoelectric (TE)-cooler.

Despite the robustness of TE-technology (including long life-time, no moving parts, etc.) and its wide range of applicability (wherever a thermal gradient exists), the TE-generators market has so far been restricted to a small number of technological areas due to their low efficiency. The thermal-to-electrical energy conversion efficiency, η of a given TE device is most often expressed as a function of a dimensionless parameter ZT, called “figure of merit”:

ZT = TSe2(σ/κ) (1).

ZT is proportional to the square of the Seebeck coefficient Se and to the ratio between the electrical (σ) and thermal (κ) conductivities. Up until 20 years ago, TE-devices had been based almost exclusively on low-gap solid-state bulk semiconductors whose ZT values are comprised in the ~0.1 – 1.0 range [1]. Compared to other heat engines (see Figure 1), there is no wonder why the TE-technology was not considered for a wider and larger-scale heat recovery applications.

Figure 1: TE-conversion efficiency as a function of ZT and heat source temperature compared to other heat engine technologies. Image taken from [2]

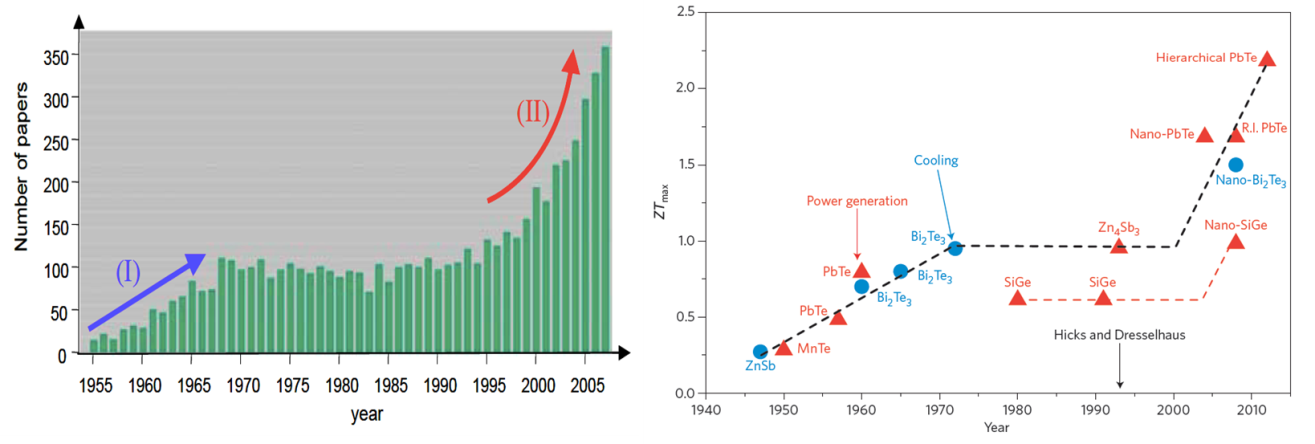

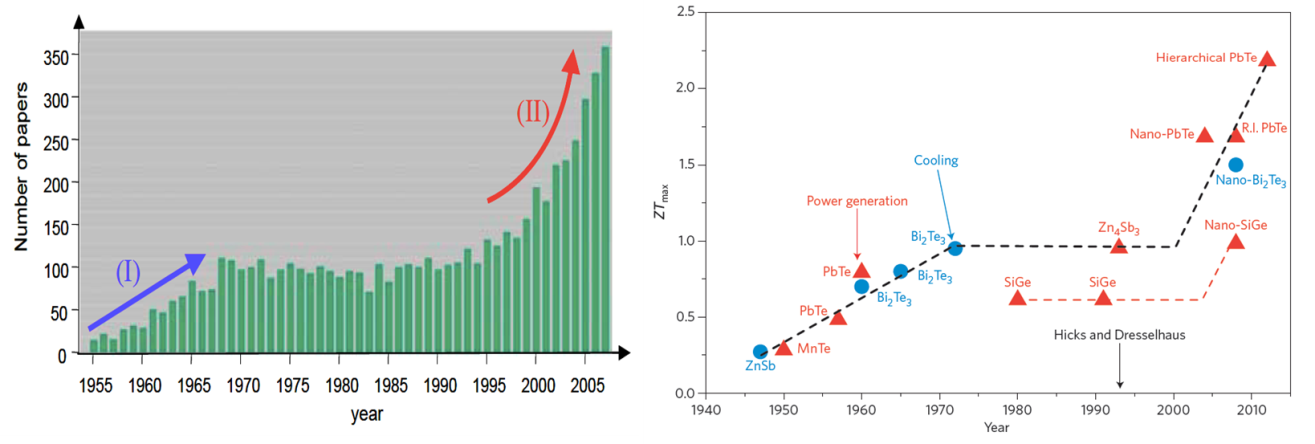

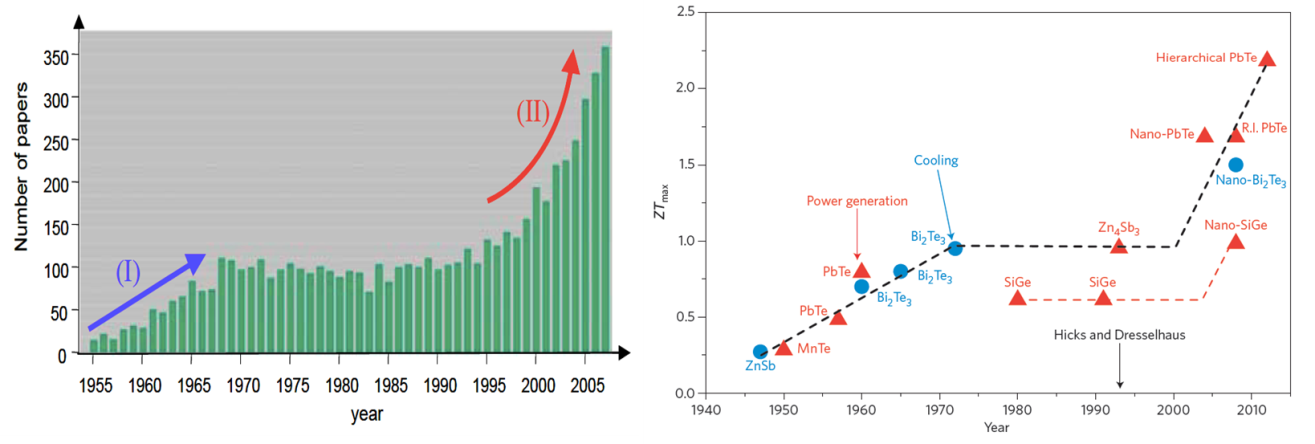

In the mid-1990’s Hicks et al., [2] predicted significant improvements in the thermoelectric efficiency in nanoscale elements. This has generated a great surge in nanostructured thermoelectric (micro)generators (See figure (left)). In a very simplified term, by ‘nano’structuring, one can reduce the material’s thermal conductivity κ, without affecting its electrical conductivity σ, resulting in an enhancement of ZT, figure of merit (see Eq. (1)).

Figure 2: (Left) Publication trend in thermoelectric research [3] and (Right) Historical progress in ZT values [4].

High ZT values (over 2 at room temperature, see Figure 2 right panel) made of bismuth-telluride and its alloys have been reported. Unfortunately, these nanostructured devices are limited to very small active surface areas and incur huge production costs. Furthermore nearly all high-performance TE materials contain rare and often toxic raw materials (high scarcity and health risks) [5], highlighting a need for a transformation thermoelectric technology made with less critical material.

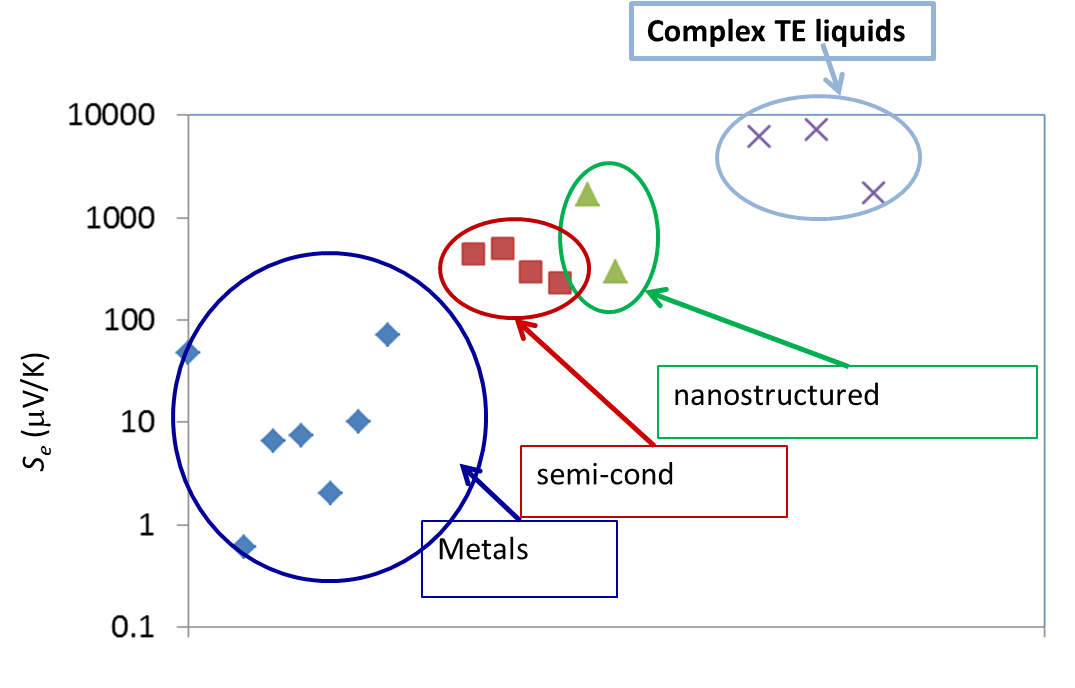

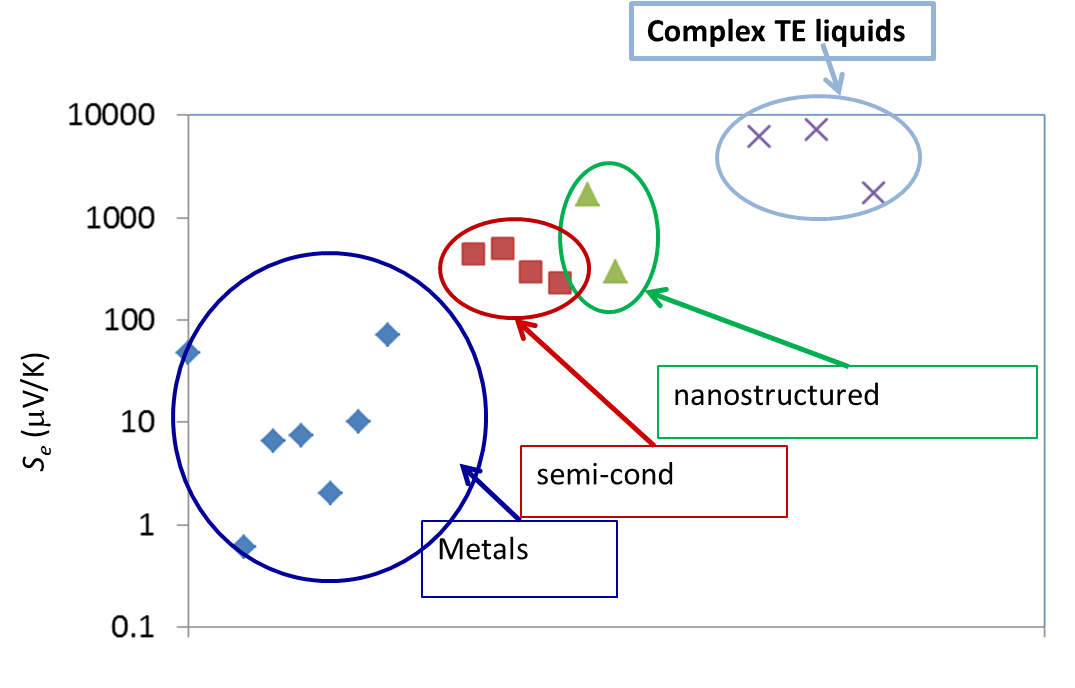

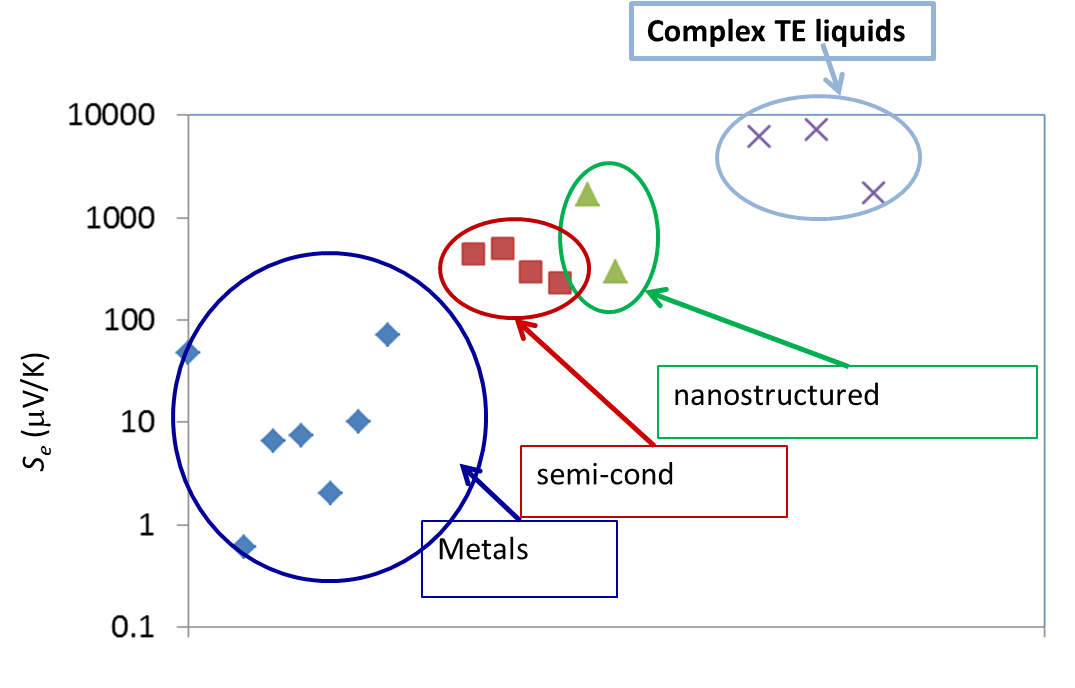

Thermoelectric effects in liquid electrolytes

Liquid electrolytes are characterised by the presence of several ion species (dissolved in a liquid matrix) and their "thermoelectric" effects have been known since the end of the 19th century. The observed TE-coefficients in electrolytes are generally an order of magnitude larger that the semiconductor counterparts, including nanostructured materials (see Figure 3 below). The electrical conductivity of these liquids, however, is a few orders of magnitude lower than solid counterparts and therefore, liquid based TE-systems have long been considered technologically irrelevant despite their advantages; e.g., material abundance, low production costs, etc..

Figure 3: Comparison of TE voltage (open circuit) of different materials

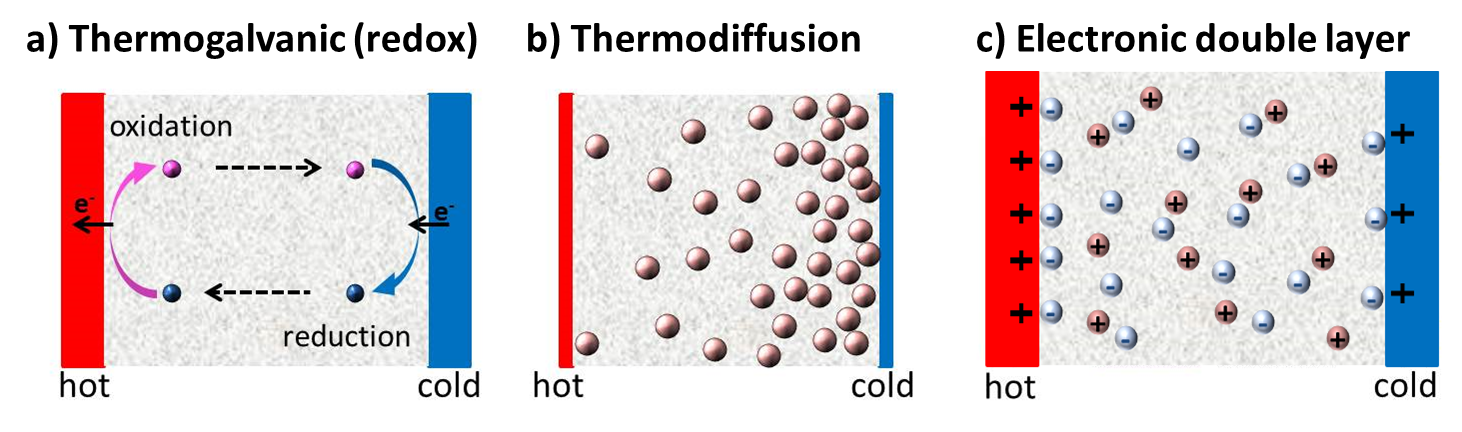

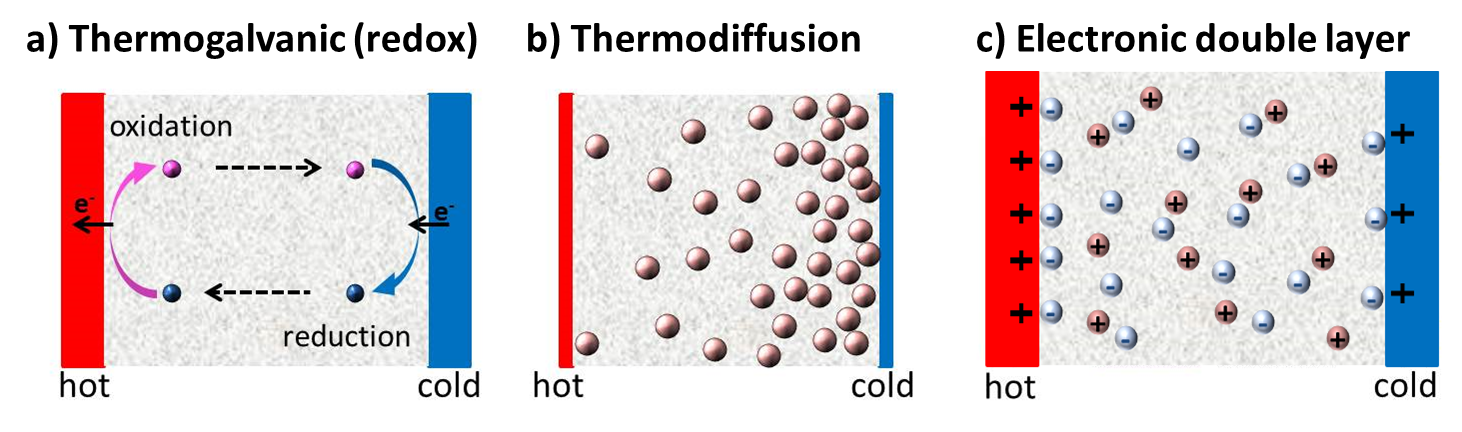

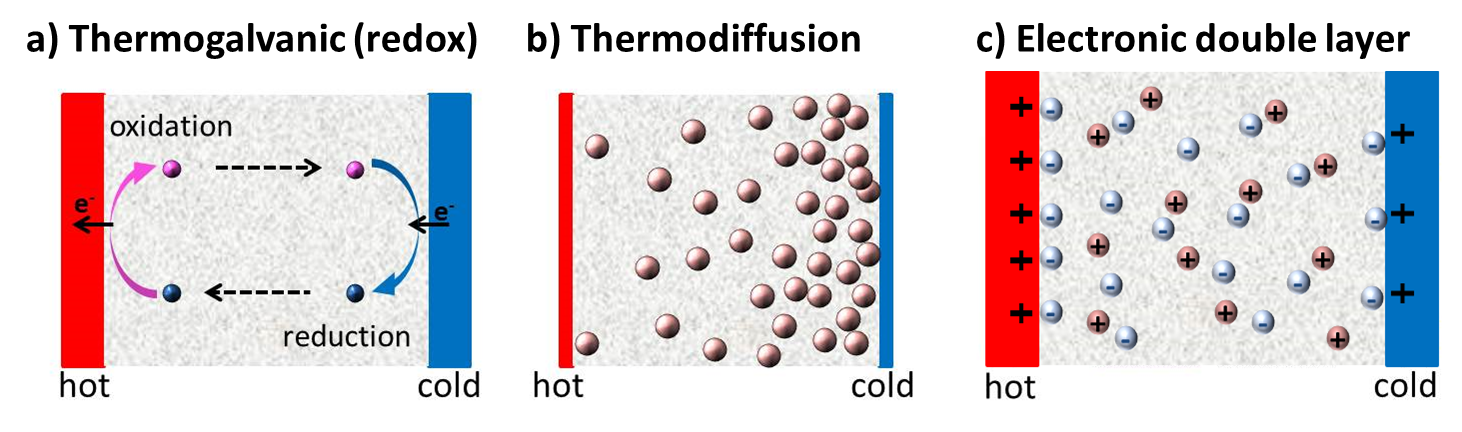

Since the discovery of TE-effects in complex liquids such as ionic-liquids/solvent binary mixtures, and charged colloidal and macromolecular suspensions, such perception surrounding liquid thermoelectrics is changing in recent years. Broadly speaking, there are 3 different sources of thermoelectric power in electrolyte containing thermoelectric cells; namely, (a) Thermogalvanic effect b) thermodiffusion of ionic species and c) Selective ion attachments of ionic species to the hot and cold electrodes.

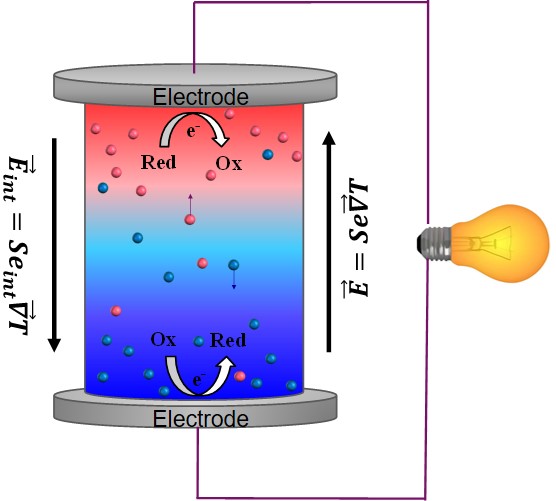

- Thermogalvanic effect: Also known as 'thermoelectrochemical effect,’ relies on redox molecules to reversibly exchange electrons (oxidation-reduction mechanism) with hot-and cold electrodes to produce large reaction entropy change; i.e., thermogalvanic-voltage. The redox couples not only serve to produce ‘voltage’ but are responsible for producing electric current in a thermocells by exchanging electrons with hot and cold electrodes. Typically observed Seebeck coefficient in thermogalvanic cells containing ILs and other liquid electrolytes is about 1 mV/K an order of magnitude larger that the semiconductor counterparts, including nanostructured materials.

- Thermodiffusion effect: The TE-effect in complex liquids (electrolytes, ionic liquids, colloidal solutions etc.) is further coupled to the movement of dissolved charged species (ions, molecules or colloidal particles) and is closely related to the “Soret effect” which describes the concentration gradients, ni induced by a temperature gradient; (Δni/ni) = αiΔT, where a is called “Soret coefficient.” The Soret effect or “thermophoresis” has been extensively studied in the last decades [16-18] and is often used for microfluidic characterization and separation. The Soret coefficient, a, is generally proportional to the entropy transported by the moving molecules or particles (i.e., internal degrees of freedom, large solvation shell, particle/molecule size, etc.). Therefore, large thermoelectric coefficients can be expected in complex liquids exhibiting large values of .

- Electronic double layer (EDL): Closely related to the thermodiffusion effect described above, the assymetric distribution of ionic species at the hot and cold electrodes can result in the temperature dependent electronic double layer capacitance at the liquid/electrode interfaces.

Figure 4: Different mechanisms at the origin of thermoelectric voltage in liquid electrolytes.

While these effects are independently known to exist in liquid electrolytes and complex liquids (such as colloidal suspensions and ionic liquids), the interdependency among thermogalvanic-thermodiffusion-EDL effect is still in the basic research phase. At SPHYNX, we are exploring these novel thermoelectric phenomena in various complex liquids.

We focus on ....

- Non-aqueous electrolytes: We have measured thermoelectric power in various non-aqueous electrolytes (alocohols, organic solvents) where TE voltage as high as 7mV/K has been measured [7]

- Ionic liquids: We investigate all 3 TE effects either in TE-generator or in TE-capacitor mode. [8, 9]

- Ferrofluids: In 2015, we have reported a first-of-its-kind experimental study on the coupled thermodiffusion and thermoelectric effects in ferrofluids based on organic solvents [10] and on water [11]. This work served as a true proof-of-principle, demonstrating the contribution of thermodiffusion of charged colloidal particles to the total thermoelectric voltage of the carrier fluid. Experimental parameters such as magnetic volume fraction, particle size, applied magnetic field strength and its direction that can be tuned to control the TE property of ferrofluids. The magnetic nature of particles further encourages the use of ferrofluids for magneto-thermoelectric energy conversion applications.

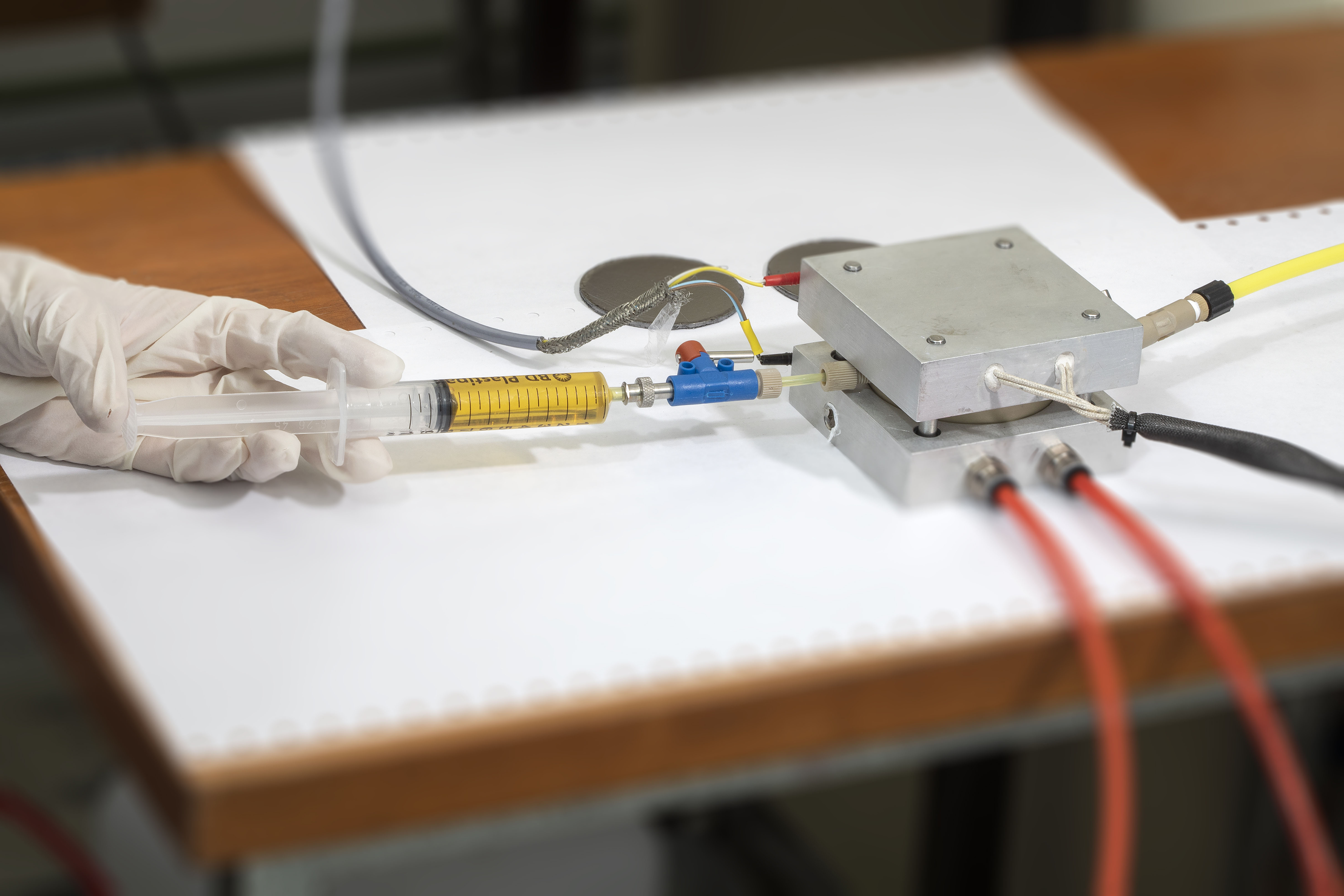

- Develop novel thermoelectric measurement techniques at high (above 150°C) and low (below 0°C) temperatures and under magnetic field.

|

Mock-up TE-cell (by CTECH Innovation in MAGENTA) |

Simplified TE-cell |

High-temperature cell |

Electrical conductivity cell |

Cette thématique pluridisciplinaire fait partie intégrante du domaine de l’électronique organique. Elle fait appel, entre autres, aux compétences relevant des domaines de la chimie et physico-chimie, de la physique des semi-conducteurs et de la caractérisation optique et électrique de dispositifs électroniques. Cet axe de recherche propose le design moléculaire, la synthèse, la caractérisation et l’utilisation de matériaux innovants comme composants actifs de diodes électroluminescentes organiques. Certains de ces matériaux contiennent des ions lanthanides qui possèdent des couleurs d’émission dans le visible et le proche infra-rouge d’une pureté incomparable. Les applications de ces dispositifs opto-électroniques sont très variées, elles vont de l’éclairage aux appareils à visée nocturne, en passant par le balisage et les écrans ultra-plats. En particulier, la très grande légèreté des dispositifs que ces matériaux permettent d’élaborer en fait des éléments de choix pour l’électronique embarquée.

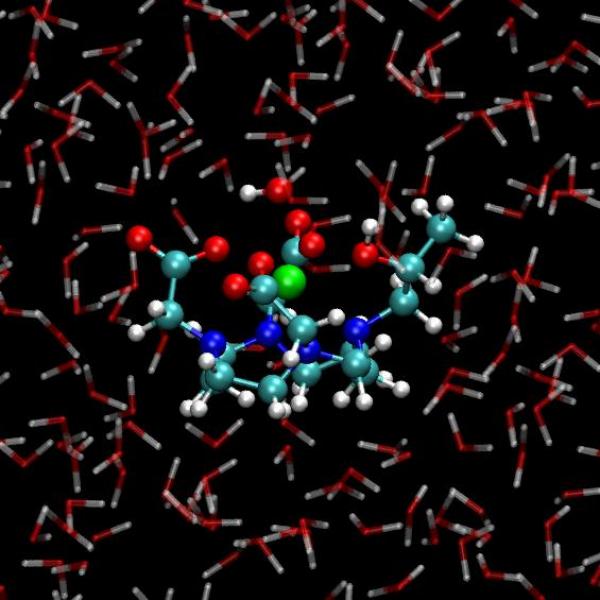

L’imagerie par résonance magnétique (IRM) nucléaire est une technique de diagnostic (notamment de tumeurs cérébrales) dont la haute résolution spatiale est assurée par l’utilisation de produits de contraste qui sont majoritairement des complexes de gadolinium. Cet ion paramagnétique accélère en effet la relaxation des protons environnants (en première voire deuxième sphère de coordination), ce qui entraîne une augmentation du contraste de l’image.

Les agents de contraste actuels manquent cependant d’efficacité, ce qui entraîne des doses importantes lors des injections, et sont incapables de cibler tel ou tel environnement physicochimique (pH, présence d’une enzyme, etc.). Les chimistes qui cherchent des agents de contraste de nouvelle génération se heurtent aux incertitudes quant aux mécanismes d’action des produits existants. Des raisonnements reposant sur des gênes stériques sont souvent invoqués au moment de leur conception alors que des facteurs moins accessibles tels que l’influence des réseaux de liaisons hydrogène au voisinage de ces complexes métalliques sont ignorés ou sous-estimés. Les simulations ab initio a l’échelle atomique que nous avons menées au cours de ces dernières années [1, 2] montrent l’importance de ces réseaux et de leur dynamique vis-à-vis de l’échange de molécules d’eau en première sphère de coordination et dans le solvant, dont la constante de temps est un paramètre modifiant significativement le temps de relaxation mesuré en IRM.

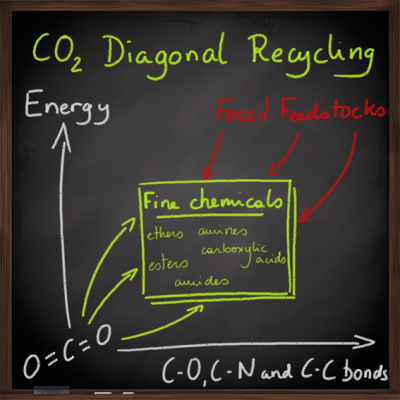

Les énergies fossiles (pétrole, gaz et charbon) représentent 85 % des besoins énergétiques mondiaux et leurs combustions constituent la première source d’émission de gaz à effets de serre notamment pour le dioxyde de carbone (CO2). Dans les prochaines décennies, les industries fortement consommatrices de ces ressources fossiles, comme celles de la chimie et des carburants, vont faire face à des défis importants pour minimiser leur impact environnemental. Elles devront ainsi utiliser des sources de carbones renouvelables. Pour résoudre cette antinomie entre les aspects économiques et écologiques, de nouvelles méthodes de recyclage du CO2 doivent être découvertes, afin d’utiliser ce déchet comme source primaire de carbone pour la production de consommables organiques (plastiques, engrais, …) et pour la production de carburants basés sur les énergies décarbonées.

Pour répondre à ces problématiques, le Laboratoire de Chimie Moléculaire et Catalyse pour l'Energie (LCMCE) du NIMBE porte une thématique visant le développement de nouveaux catalyseurs et procédés catalytiques pour le recyclage chimique du CO2.

Les membranes nanostructurées peuvent être utilisées dans le domaine du médical, de l’environnement et de l’énergie. Ce type de membranes dites “Track-etched” sont créées par révélation chimique de traces induites par pré-irradiation aux ions lourds accélérés du GANIL Grâce à sa connaissance aigüe de l’interaction électron-polymère par irradiation aux électrons, le LSI est capable de prévoir le comportement du greffage radio-induit de monomères vinyliques dans les traces. Il maîtrise également la polymérisation oxydative de polypyrrole dans les traces, permettant ainsi de former des réseaux de nanotubes de polymères conducteurs. Toutes ces structures servent notamment à l’étude fondamentale de la conduction à l’échelle nanométrique (applications capteurs, optoélectroniques, électronique de spin), ainsi qu’à l’étude de la conduction ionique dans des nanocanaux remplis de polyélectrolytes (application Piles à combustibles de type polymère).

L’imagerie par résonance magnétique (IRM) nucléaire est une technique de diagnostic (notamment de tumeurs cérébrales) dont la haute résolution spatiale est assurée par l’utilisation de produits de contraste qui sont majoritairement des complexes de gadolinium. Cet ion paramagnétique accélère en effet la relaxation des protons environnants (en première voire deuxième sphère de coordination), ce qui entraîne une augmentation du contraste de l’image.

Les agents de contraste actuels manquent cependant d’efficacité, ce qui entraîne des doses importantes lors des injections, et sont incapables de cibler tel ou tel environnement physicochimique (pH, présence d’une enzyme, etc.). Les chimistes qui cherchent des agents de contraste de nouvelle génération se heurtent aux incertitudes quant aux mécanismes d’action des produits existants. Des raisonnements reposant sur des gênes stériques sont souvent invoqués au moment de leur conception alors que des facteurs moins accessibles tels que l’influence des réseaux de liaisons hydrogène au voisinage de ces complexes métalliques sont ignorés ou sous-estimés. Les simulations ab initio a l’échelle atomique que nous avons menées au cours de ces dernières années [1, 2] montrent l’importance de ces réseaux et de leur dynamique vis-à-vis de l’échange de molécules d’eau en première sphère de coordination et dans le solvant, dont la constante de temps est un paramètre modifiant significativement le temps de relaxation mesuré en IRM.

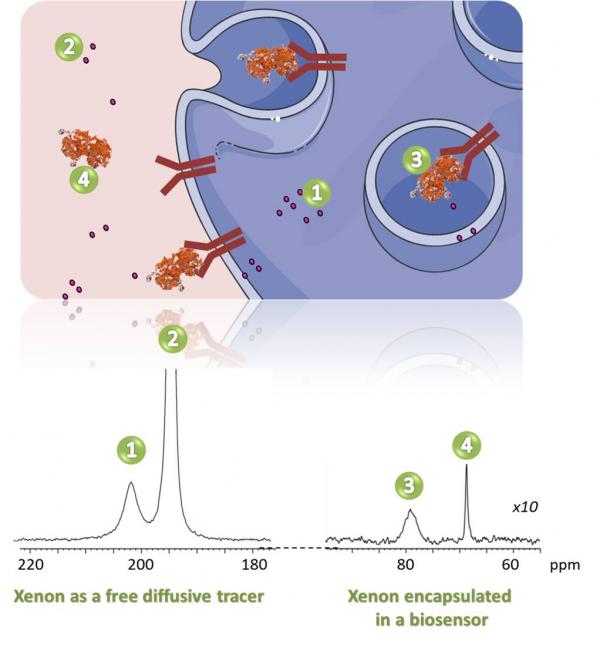

Le 129Xe hyperpolarisé peut être utilisé dans des suspensions cellulaires selon deux stratégies différentes :

- Seul, en tant que traceur diffusif libre. Le xénon pénètre dans les cellules en ~30 ms sans perdre son hyperpolarisation. L'interaction du xénon avec les cellules vivantes donne lieu à un signal RMN spécifique dans la région des 200 ppm. Le déplacement chimique et l'intensité de ce signal sont corrélés à la nature de la lignée cellulaire, à la viabilité et à la densité.

- Encapsulé dans une molécule hôte pour détecter un mécanisme biologique spécifique, par exemple le processus d'internalisation de la transferrine. Le biocapteur a été obtenu en greffant des parties de cryptophane à la transferrine.

Hyperpolarized 129Xe can be used in cell suspensions using two different strategies:

- Alone, as a free diffusive tracer. Xenon enters in the cells in ~30 ms without losing its hyper-polarization. Xenon interacting with living cells gives rise to a specific NMR signal in the 200 ppm region. The chemical shift and the intensity of this signal are correlated to the nature of the cell line, the viability and density.

- Encapsulated in a host molecule to detect a specific biological mechanism, for instance, the internalization process of transferrin. The biosensor has been obtained by the grafting of cryptophane moieties to the transferrin.

2007 - today

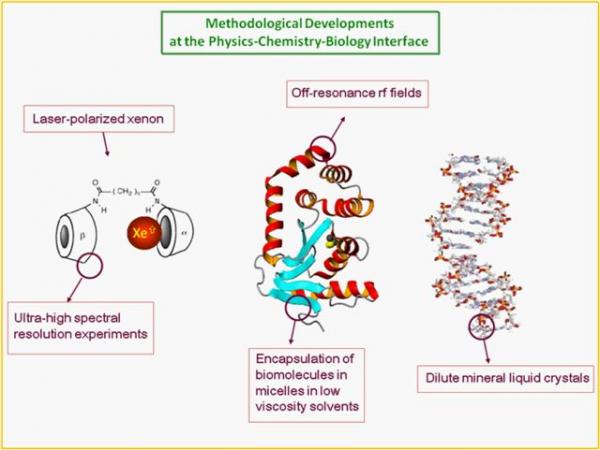

- Hyperpolarized species for NMR/MRI

- Interatomic distance measurement using 3H solid-state NMR

- Developments for metabolomics

1999 - 2007

Production

-

Animation for PC (S. Jubera)

-

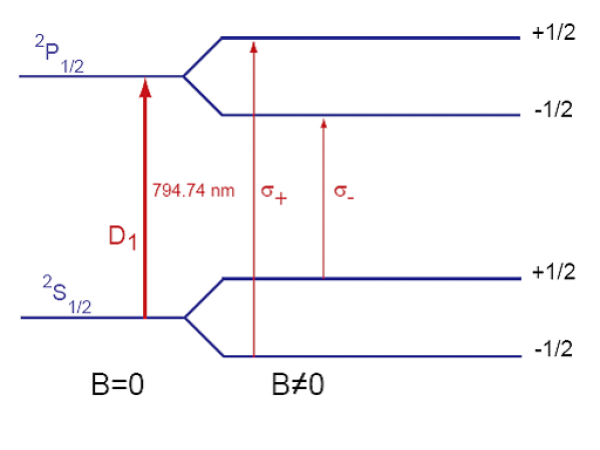

Two optical pumping setups have been built:

-

the first one based on a Titanium:Sapphire laser

-

the second one using laser diodes

-

High resolution NMR fails in the case of large macromolecules (molecular size >35 kDa) due to slow tumbling which results in short relaxation time T2 and signal loss during pulse sequences, even for proteins enriched in stable isotopes (15N, 13C, 2H), and in spite of the experiments using cross correlation effects (TROSY, CRINEPT).

To gain insight in the long-term behavior of nuclear waste packages at the glass–metal–clay interfaces in their geological repository conditions, slags from ancient ironmaking sites can be used as valuable proxies.

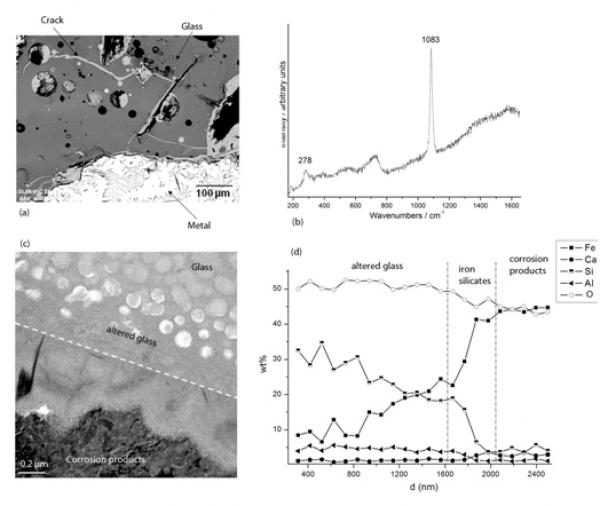

The question of the interaction between glass and iron is particularly important because nuclear glasses are poured in a stainless steel canister and the resulting package is expected to be surrounded by a thick carbon steel overpack (Andra, 2005). Some laboratory experiments under anoxic conditions have shown that the presence of iron and more generally iron corrosion products sustain glass alteration at a rate higher than the glass would undergo in the presence of site water only. This enhancement of glass alteration is due to the strong affinity of iron rich phases with respect to silicon, the main component of the glass (De Combarieu, et al., 2010 in press, Jollivet, et al., 2000). It has been asserted that the formation of Fe-Si containing phase delay the formation of the protective gel layer responsible for the drop of alteration rate observed in glasses altered by water under static or low flow rate conditions (Combarieu, et al., 2010 in press). That is why understanding and modeling interactions between glass, iron and clay is a key preliminary step in order to predict long-term behavior of nuclear glass packages. Consequently, studies of natural or archaeological analogues give precious observational insight for this issue. For example, the site of Glinet dated from the 16th century (Neff, et al., 2010), has been taken as a reference site for studying glass/iron interactions. Indeed, the by-product slags produced by the blast furnace present partly glassy matrix and contain metallic particles of micrometric to millimetric sizes. The blocks present numerous cracks that were immediately saturated with water as they were buried at depths continuously under the water level. It has been verified by on-field measurements and laboratory tests that at the sample location, water was carbonated and anoxic (Saheb, et al., in press). Moreover the crack network connects the metallic zones of the slags to the external solution of the soil and is entirely filled by corrosion products of iron such as those found in desaerated media (Fig. a). Microstructural characterization of the network embedded with the corrosion products by µRaman spectroscopy, reveal the presence of siderite (FeCO3- Fig b). This siderite contains several % of calcium partially substituting the Fe atoms. This substitution was also observed on iron artefacts corroded in the same medium and could come from the groundwater but also, in the present case, from the glass matrix, that contain this element. Actually, the glasses identified in Glinet are calcium silicate glass rich in iron and aluminum (%masMgO: 0.7-2.2, %masAl2O3: 5.1-8.8, %masSiO2: 61.9-76.5, K2O: 1.8-2.3, %masCaO: 15.6-25.1, %masMnO: 0.2-2.9, %masFeO: 1.2-9.1). This range of compositions for the ternary CaO-A2O3-SiO2 defines an area known for its immiscibility (Neuville 2006). SEM-FEG observations confirm a non-homogeneous nanostructure characterized by the presence of spheroids of several hundreds of nanometers distributed in a glass matrix. This specific structure of the glass implies different alteration kinetics for each of the phases observed by TEM (Fig c). The spheroids, mainly constituted of SiO2, are less altered than the embedding matrix containing higher concentration the other elements.

At the interface between glass and iron corrosion products, different layers have been observed, linked to the variation of composition (Figc and Figd). EDS analyses coupled to STEM indicate that the altered glass is depleted in Ca but not in Al. Interestingly, an external festooned layer between altered glass and siderite, made of amorphous iron silicates is observed (Figc). The study of this layer can give insight into the influence of iron on the glass corrosion. Moreover, iron coming from the metal corrosion products has penetrated into the altered layers of the glass. Laboratory experiments simulating a crack, have been conducted for 120 days at 50°C on synthetised glass samples with the structure and the chemical composition of the slag glass matrix. The chemical profiles of the glass alteration layers are very comparable to the archaeological ones and are currently under study, The results are expected to help discriminating between the controlling parameters of glass alteration: transport vs chemical equilibria.

Three wrought iron ingots immersed during 2000 years at 12 m deep in Mediterranean Sea were stored after excavation for 2 years without specific protection in air. After that period, two of them were treated by immersion in a NaOH solution, while the third was used to describe the corrosion system resulting from the storage conditions. This characterisation was achieved by a combination of microanalytical techniques. It could be concluded that though ferrous hydroxychloride β-Fe2(OH)3Cl was the main Cl containing phase at the time of excavation, akaganeite [β-FeO1-x(OH)1+xClx] was the only one present in the rust layers after storage. In order to determine the influence of corrosion products nature on dechlorination treatment, the evolution of a corrosion system composed of both Cl containing phases β-FeOOH and β-Fe2(OH)3Cl has been followed during in situ NaOH experimental treatment. Specific behaviours of each phase to the dechlorination treatment have been revealed.

Influence of corrosion products nature on dechlorination treatment: case of wrought iron archaeological ingots stored 2 years in air before NaOH treatment,

F. Kergourlay; E. Guilminot; D. Neff; C. Remazeilles; S. Reguer; P. Refait; F. Mirambet; E. Foy; P. Dillmann, Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 45, (2010) 407-413.

Welcome to Complex Liquid Thermoelectrics Research group

NEW!!! Internship position (4-6 months, experimental) for thermally chargeable supercapacitor develoment and characterization

M2 level, starting Feb/March 2020. Possible continuation as a PhD candidate from Fall 2020.

To know more click HERE

Who & What

We study thermal-to-electrical energy conversion phenomena in liquids by combining experimental techniques from physics, physical chemistry and electrochemistr. It is an exciting new field of research that is attracting increased attention as an alternative solution to semi-conductor based thermoelectric materials. The underlying physics , the types of complex liquids and possible future application paths are described below.

Also....

Please visit our MAGENTA project page https://www.magenta-h2020.eu

A member of NANOUPTAKE– Overcoming Barriers to Nanofluids Market Uptake (COST Action CA15119)

Thermoelectricity at a glance

The application of a temperature difference ΔT across a solid conductor causes mobile charge carriers to diffuse from hot to cold region, giving rise to a thermoelectric voltage V = -Se∆T. The prefactor Se is called th thermopower or Seebeck coefficient since the discovery of this phenomenon by Seebeck in 1821. This enables the conversion of heat to electricity.

In ordinary metals like copper, the Seebeck coefficient Se is of the order of 10 μV/K. In the mid 20th century much higher Seebeck coefficients of a few hundreds of μV/K were obtained in low-gap semi-conductors, and those materials are still the object of intense research activities, with the perspective of converting low-grade wasted heat; e.g., body heat, car exhausts, industrial waste streams, solar heating, etc., into electric energy. Conversely, the application of voltage ΔV results in a temperature difference (the Peltier effect) such that the same material can be used as a thermoelectric (TE)-cooler.

Despite the robustness of TE-technology (including long life-time, no moving parts, etc.) and its wide range of applicability (wherever a thermal gradient exists), the TE-generators market has so far been restricted to a small number of technological areas due to their low efficiency. The thermal-to-electrical energy conversion efficiency, η of a given TE device is most often expressed as a function of a dimensionless parameter ZT, called “figure of merit”:

ZT = TSe2(σ/κ) (1).

ZT is proportional to the square of the Seebeck coefficient Se and to the ratio between the electrical (σ) and thermal (κ) conductivities. Up until 20 years ago, TE-devices had been based almost exclusively on low-gap solid-state bulk semiconductors whose ZT values are comprised in the ~0.1 – 1.0 range [1]. Compared to other heat engines (see Figure 1), there is no wonder why the TE-technology was not considered for a wider and larger-scale heat recovery applications.

Figure 1: TE-conversion efficiency as a function of ZT and heat source temperature compared to other heat engine technologies. Image taken from [2]

In the mid-1990’s Hicks et al., [2] predicted significant improvements in the thermoelectric efficiency in nanoscale elements. This has generated a great surge in nanostructured thermoelectric (micro)generators (See figure (left)). In a very simplified term, by ‘nano’structuring, one can reduce the material’s thermal conductivity κ, without affecting its electrical conductivity σ, resulting in an enhancement of ZT, figure of merit (see Eq. (1)).

Figure 2: (Left) Publication trend in thermoelectric research [3] and (Right) Historical progress in ZT values [4].

High ZT values (over 2 at room temperature, see Figure 2 right panel) made of bismuth-telluride and its alloys have been reported. Unfortunately, these nanostructured devices are limited to very small active surface areas and incur huge production costs. Furthermore nearly all high-performance TE materials contain rare and often toxic raw materials (high scarcity and health risks) [5], highlighting a need for a transformation thermoelectric technology made with less critical material.

Thermoelectric effects in liquid electrolytes

Liquid electrolytes are characterised by the presence of several ion species (dissolved in a liquid matrix) and their "thermoelectric" effects have been known since the end of the 19th century. The observed TE-coefficients in electrolytes are generally an order of magnitude larger that the semiconductor counterparts, including nanostructured materials (see Figure 3 below). The electrical conductivity of these liquids, however, is a few orders of magnitude lower than solid counterparts and therefore, liquid based TE-systems have long been considered technologically irrelevant despite their advantages; e.g., material abundance, low production costs, etc..

Figure 3: Comparison of TE voltage (open circuit) of different materials

Since the discovery of TE-effects in complex liquids such as ionic-liquids/solvent binary mixtures, and charged colloidal and macromolecular suspensions, such perception surrounding liquid thermoelectrics is changing in recent years. Broadly speaking, there are 3 different sources of thermoelectric power in electrolyte containing thermoelectric cells; namely, (a) Thermogalvanic effect b) thermodiffusion of ionic species and c) Selective ion attachments of ionic species to the hot and cold electrodes.

- Thermogalvanic effect: Also known as 'thermoelectrochemical effect,’ relies on redox molecules to reversibly exchange electrons (oxidation-reduction mechanism) with hot-and cold electrodes to produce large reaction entropy change; i.e., thermogalvanic-voltage. The redox couples not only serve to produce ‘voltage’ but are responsible for producing electric current in a thermocells by exchanging electrons with hot and cold electrodes. Typically observed Seebeck coefficient in thermogalvanic cells containing ILs and other liquid electrolytes is about 1 mV/K an order of magnitude larger that the semiconductor counterparts, including nanostructured materials.

- Thermodiffusion effect: The TE-effect in complex liquids (electrolytes, ionic liquids, colloidal solutions etc.) is further coupled to the movement of dissolved charged species (ions, molecules or colloidal particles) and is closely related to the “Soret effect” which describes the concentration gradients, ni induced by a temperature gradient; (Δni/ni) = αiΔT, where a is called “Soret coefficient.” The Soret effect or “thermophoresis” has been extensively studied in the last decades [16-18] and is often used for microfluidic characterization and separation. The Soret coefficient, a, is generally proportional to the entropy transported by the moving molecules or particles (i.e., internal degrees of freedom, large solvation shell, particle/molecule size, etc.). Therefore, large thermoelectric coefficients can be expected in complex liquids exhibiting large values of .

- Electronic double layer (EDL): Closely related to the thermodiffusion effect described above, the assymetric distribution of ionic species at the hot and cold electrodes can result in the temperature dependent electronic double layer capacitance at the liquid/electrode interfaces.

Figure 4: Different mechanisms at the origin of thermoelectric voltage in liquid electrolytes.

While these effects are independently known to exist in liquid electrolytes and complex liquids (such as colloidal suspensions and ionic liquids), the interdependency among thermogalvanic-thermodiffusion-EDL effect is still in the basic research phase. At SPHYNX, we are exploring these novel thermoelectric phenomena in various complex liquids.

We focus on ....

- Non-aqueous electrolytes: We have measured thermoelectric power in various non-aqueous electrolytes (alocohols, organic solvents) where TE voltage as high as 7mV/K has been measured [7]

- Ionic liquids: We investigate all 3 TE effects either in TE-generator or in TE-capacitor mode. [8, 9]

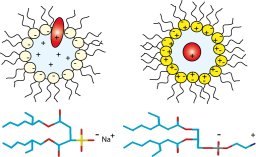

- Ferrofluids: In 2015, we have reported a first-of-its-kind experimental study on the coupled thermodiffusion and thermoelectric effects in ferrofluids based on organic solvents [10] and on water [11]. This work served as a true proof-of-principle, demonstrating the contribution of thermodiffusion of charged colloidal particles to the total thermoelectric voltage of the carrier fluid. Experimental parameters such as magnetic volume fraction, particle size, applied magnetic field strength and its direction that can be tuned to control the TE property of ferrofluids. The magnetic nature of particles further encourages the use of ferrofluids for magneto-thermoelectric energy conversion applications.

- Develop novel thermoelectric measurement techniques at high (above 150°C) and low (below 0°C) temperatures and under magnetic field.

|

Mock-up TE-cell (by CTECH Innovation in MAGENTA) |

Simplified TE-cell |

High-temperature cell |

Electrical conductivity cell |

To gain insight in the long-term behavior of nuclear waste packages at the glass–metal–clay interfaces in their geological repository conditions, slags from ancient ironmaking sites can be used as valuable proxies.

The question of the interaction between glass and iron is particularly important because nuclear glasses are poured in a stainless steel canister and the resulting package is expected to be surrounded by a thick carbon steel overpack (Andra, 2005). Some laboratory experiments under anoxic conditions have shown that the presence of iron and more generally iron corrosion products sustain glass alteration at a rate higher than the glass would undergo in the presence of site water only. This enhancement of glass alteration is due to the strong affinity of iron rich phases with respect to silicon, the main component of the glass (De Combarieu, et al., 2010 in press, Jollivet, et al., 2000). It has been asserted that the formation of Fe-Si containing phase delay the formation of the protective gel layer responsible for the drop of alteration rate observed in glasses altered by water under static or low flow rate conditions (Combarieu, et al., 2010 in press). That is why understanding and modeling interactions between glass, iron and clay is a key preliminary step in order to predict long-term behavior of nuclear glass packages. Consequently, studies of natural or archaeological analogues give precious observational insight for this issue. For example, the site of Glinet dated from the 16th century (Neff, et al., 2010), has been taken as a reference site for studying glass/iron interactions. Indeed, the by-product slags produced by the blast furnace present partly glassy matrix and contain metallic particles of micrometric to millimetric sizes. The blocks present numerous cracks that were immediately saturated with water as they were buried at depths continuously under the water level. It has been verified by on-field measurements and laboratory tests that at the sample location, water was carbonated and anoxic (Saheb, et al., in press). Moreover the crack network connects the metallic zones of the slags to the external solution of the soil and is entirely filled by corrosion products of iron such as those found in desaerated media (Fig. a). Microstructural characterization of the network embedded with the corrosion products by µRaman spectroscopy, reveal the presence of siderite (FeCO3- Fig b). This siderite contains several % of calcium partially substituting the Fe atoms. This substitution was also observed on iron artefacts corroded in the same medium and could come from the groundwater but also, in the present case, from the glass matrix, that contain this element. Actually, the glasses identified in Glinet are calcium silicate glass rich in iron and aluminum (%masMgO: 0.7-2.2, %masAl2O3: 5.1-8.8, %masSiO2: 61.9-76.5, K2O: 1.8-2.3, %masCaO: 15.6-25.1, %masMnO: 0.2-2.9, %masFeO: 1.2-9.1). This range of compositions for the ternary CaO-A2O3-SiO2 defines an area known for its immiscibility (Neuville 2006). SEM-FEG observations confirm a non-homogeneous nanostructure characterized by the presence of spheroids of several hundreds of nanometers distributed in a glass matrix. This specific structure of the glass implies different alteration kinetics for each of the phases observed by TEM (Fig c). The spheroids, mainly constituted of SiO2, are less altered than the embedding matrix containing higher concentration the other elements.

At the interface between glass and iron corrosion products, different layers have been observed, linked to the variation of composition (Figc and Figd). EDS analyses coupled to STEM indicate that the altered glass is depleted in Ca but not in Al. Interestingly, an external festooned layer between altered glass and siderite, made of amorphous iron silicates is observed (Figc). The study of this layer can give insight into the influence of iron on the glass corrosion. Moreover, iron coming from the metal corrosion products has penetrated into the altered layers of the glass. Laboratory experiments simulating a crack, have been conducted for 120 days at 50°C on synthetised glass samples with the structure and the chemical composition of the slag glass matrix. The chemical profiles of the glass alteration layers are very comparable to the archaeological ones and are currently under study, The results are expected to help discriminating between the controlling parameters of glass alteration: transport vs chemical equilibria.

Three wrought iron ingots immersed during 2000 years at 12 m deep in Mediterranean Sea were stored after excavation for 2 years without specific protection in air. After that period, two of them were treated by immersion in a NaOH solution, while the third was used to describe the corrosion system resulting from the storage conditions. This characterisation was achieved by a combination of microanalytical techniques. It could be concluded that though ferrous hydroxychloride β-Fe2(OH)3Cl was the main Cl containing phase at the time of excavation, akaganeite [β-FeO1-x(OH)1+xClx] was the only one present in the rust layers after storage. In order to determine the influence of corrosion products nature on dechlorination treatment, the evolution of a corrosion system composed of both Cl containing phases β-FeOOH and β-Fe2(OH)3Cl has been followed during in situ NaOH experimental treatment. Specific behaviours of each phase to the dechlorination treatment have been revealed.

Influence of corrosion products nature on dechlorination treatment: case of wrought iron archaeological ingots stored 2 years in air before NaOH treatment,

F. Kergourlay; E. Guilminot; D. Neff; C. Remazeilles; S. Reguer; P. Refait; F. Mirambet; E. Foy; P. Dillmann, Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 45, (2010) 407-413.

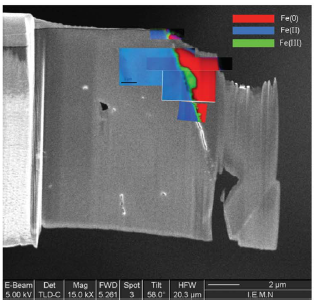

Prediction of long term corrosion (on several hundred years) of low alloy steels is a crucial issue in several research domains: metallic cultural heritage conservation, civil engeeniring, etc. Recent results demonstrate that, despite the corrosion layers could reach several millimetre thicknesses, the kinetics can be controlled at the nanoscale (presence of barrier layer at the metal/oxide interface, influence of crystallinity in the electrochemical reactivity, etc). For that reason, in addition to micrometer scale investigation it is now necessary to characterise these complex systems at the nanometer scale. In addition to classical TEM methods, the appearance of new synchrotron based techniques as Scanning Transmission Xray Microsopy, opens the door to new kind of chemical (atoms environments) and structural investigations at the nanoscale, in the field of corrosion.

First investigations were conducted iron nails, coming from the 16th century archaeological site of Glinet. This site is a reference one for long term corrosion studies since about 10 years and present desaerated calco-carbonated water saturated soil. The metal oxide interface was investigated, focusing on the detection on specific barrier layers that could play a crucial role in the corrosion mechanisms..

After classical observations at the microscopic scale (SEM, µRaman spectroscopy,...) both samples sets, (were observed on thin films of the transverse sections prepared by FIB. A fine elementary and structural description of the interfaces between metal and corrosion products in the nails has been obtained by TEM- and STXM. Chemical and structural maps (atom environments) were provided at the nanoscale. STXM experiments have been performed at Pollux beamline at Swiss Light Source synchrotron on these alteration layers in order to determine the nature of the phases formed.

Welcome to Complex Liquid Thermoelectrics Research group

NEW!!! Internship position (4-6 months, experimental) for thermally chargeable supercapacitor develoment and characterization

M2 level, starting Feb/March 2020. Possible continuation as a PhD candidate from Fall 2020.

To know more click HERE

Who & What

We study thermal-to-electrical energy conversion phenomena in liquids by combining experimental techniques from physics, physical chemistry and electrochemistr. It is an exciting new field of research that is attracting increased attention as an alternative solution to semi-conductor based thermoelectric materials. The underlying physics , the types of complex liquids and possible future application paths are described below.

Also....

Please visit our MAGENTA project page https://www.magenta-h2020.eu

A member of NANOUPTAKE– Overcoming Barriers to Nanofluids Market Uptake (COST Action CA15119)

Thermoelectricity at a glance

The application of a temperature difference ΔT across a solid conductor causes mobile charge carriers to diffuse from hot to cold region, giving rise to a thermoelectric voltage V = -Se∆T. The prefactor Se is called th thermopower or Seebeck coefficient since the discovery of this phenomenon by Seebeck in 1821. This enables the conversion of heat to electricity.

In ordinary metals like copper, the Seebeck coefficient Se is of the order of 10 μV/K. In the mid 20th century much higher Seebeck coefficients of a few hundreds of μV/K were obtained in low-gap semi-conductors, and those materials are still the object of intense research activities, with the perspective of converting low-grade wasted heat; e.g., body heat, car exhausts, industrial waste streams, solar heating, etc., into electric energy. Conversely, the application of voltage ΔV results in a temperature difference (the Peltier effect) such that the same material can be used as a thermoelectric (TE)-cooler.

Despite the robustness of TE-technology (including long life-time, no moving parts, etc.) and its wide range of applicability (wherever a thermal gradient exists), the TE-generators market has so far been restricted to a small number of technological areas due to their low efficiency. The thermal-to-electrical energy conversion efficiency, η of a given TE device is most often expressed as a function of a dimensionless parameter ZT, called “figure of merit”:

ZT = TSe2(σ/κ) (1).

ZT is proportional to the square of the Seebeck coefficient Se and to the ratio between the electrical (σ) and thermal (κ) conductivities. Up until 20 years ago, TE-devices had been based almost exclusively on low-gap solid-state bulk semiconductors whose ZT values are comprised in the ~0.1 – 1.0 range [1]. Compared to other heat engines (see Figure 1), there is no wonder why the TE-technology was not considered for a wider and larger-scale heat recovery applications.

Figure 1: TE-conversion efficiency as a function of ZT and heat source temperature compared to other heat engine technologies. Image taken from [2]

In the mid-1990’s Hicks et al., [2] predicted significant improvements in the thermoelectric efficiency in nanoscale elements. This has generated a great surge in nanostructured thermoelectric (micro)generators (See figure (left)). In a very simplified term, by ‘nano’structuring, one can reduce the material’s thermal conductivity κ, without affecting its electrical conductivity σ, resulting in an enhancement of ZT, figure of merit (see Eq. (1)).

Figure 2: (Left) Publication trend in thermoelectric research [3] and (Right) Historical progress in ZT values [4].

High ZT values (over 2 at room temperature, see Figure 2 right panel) made of bismuth-telluride and its alloys have been reported. Unfortunately, these nanostructured devices are limited to very small active surface areas and incur huge production costs. Furthermore nearly all high-performance TE materials contain rare and often toxic raw materials (high scarcity and health risks) [5], highlighting a need for a transformation thermoelectric technology made with less critical material.

Thermoelectric effects in liquid electrolytes

Liquid electrolytes are characterised by the presence of several ion species (dissolved in a liquid matrix) and their "thermoelectric" effects have been known since the end of the 19th century. The observed TE-coefficients in electrolytes are generally an order of magnitude larger that the semiconductor counterparts, including nanostructured materials (see Figure 3 below). The electrical conductivity of these liquids, however, is a few orders of magnitude lower than solid counterparts and therefore, liquid based TE-systems have long been considered technologically irrelevant despite their advantages; e.g., material abundance, low production costs, etc..

Figure 3: Comparison of TE voltage (open circuit) of different materials

Since the discovery of TE-effects in complex liquids such as ionic-liquids/solvent binary mixtures, and charged colloidal and macromolecular suspensions, such perception surrounding liquid thermoelectrics is changing in recent years. Broadly speaking, there are 3 different sources of thermoelectric power in electrolyte containing thermoelectric cells; namely, (a) Thermogalvanic effect b) thermodiffusion of ionic species and c) Selective ion attachments of ionic species to the hot and cold electrodes.

- Thermogalvanic effect: Also known as 'thermoelectrochemical effect,’ relies on redox molecules to reversibly exchange electrons (oxidation-reduction mechanism) with hot-and cold electrodes to produce large reaction entropy change; i.e., thermogalvanic-voltage. The redox couples not only serve to produce ‘voltage’ but are responsible for producing electric current in a thermocells by exchanging electrons with hot and cold electrodes. Typically observed Seebeck coefficient in thermogalvanic cells containing ILs and other liquid electrolytes is about 1 mV/K an order of magnitude larger that the semiconductor counterparts, including nanostructured materials.

- Thermodiffusion effect: The TE-effect in complex liquids (electrolytes, ionic liquids, colloidal solutions etc.) is further coupled to the movement of dissolved charged species (ions, molecules or colloidal particles) and is closely related to the “Soret effect” which describes the concentration gradients, ni induced by a temperature gradient; (Δni/ni) = αiΔT, where a is called “Soret coefficient.” The Soret effect or “thermophoresis” has been extensively studied in the last decades [16-18] and is often used for microfluidic characterization and separation. The Soret coefficient, a, is generally proportional to the entropy transported by the moving molecules or particles (i.e., internal degrees of freedom, large solvation shell, particle/molecule size, etc.). Therefore, large thermoelectric coefficients can be expected in complex liquids exhibiting large values of .

- Electronic double layer (EDL): Closely related to the thermodiffusion effect described above, the assymetric distribution of ionic species at the hot and cold electrodes can result in the temperature dependent electronic double layer capacitance at the liquid/electrode interfaces.

Figure 4: Different mechanisms at the origin of thermoelectric voltage in liquid electrolytes.

While these effects are independently known to exist in liquid electrolytes and complex liquids (such as colloidal suspensions and ionic liquids), the interdependency among thermogalvanic-thermodiffusion-EDL effect is still in the basic research phase. At SPHYNX, we are exploring these novel thermoelectric phenomena in various complex liquids.

We focus on ....

- Non-aqueous electrolytes: We have measured thermoelectric power in various non-aqueous electrolytes (alocohols, organic solvents) where TE voltage as high as 7mV/K has been measured [7]

- Ionic liquids: We investigate all 3 TE effects either in TE-generator or in TE-capacitor mode. [8, 9]

- Ferrofluids: In 2015, we have reported a first-of-its-kind experimental study on the coupled thermodiffusion and thermoelectric effects in ferrofluids based on organic solvents [10] and on water [11]. This work served as a true proof-of-principle, demonstrating the contribution of thermodiffusion of charged colloidal particles to the total thermoelectric voltage of the carrier fluid. Experimental parameters such as magnetic volume fraction, particle size, applied magnetic field strength and its direction that can be tuned to control the TE property of ferrofluids. The magnetic nature of particles further encourages the use of ferrofluids for magneto-thermoelectric energy conversion applications.

- Develop novel thermoelectric measurement techniques at high (above 150°C) and low (below 0°C) temperatures and under magnetic field.

|

Mock-up TE-cell (by CTECH Innovation in MAGENTA) |

Simplified TE-cell |

High-temperature cell |

Electrical conductivity cell |